-

When preparing the mandate for the negotiations on TTIP, and in the first important months of the talks themselves (January 2012 to February 2014), the European Commission’s trade department (DG Trade) had 597 behind-closed-door meetings with lobbyists to discuss the negotiations, according to internal Commission files obtained via access to information requests. 528 of those meetings (88%) were with business lobbyists while only 53 (9%) were with public interest groups. So, for every meeting with a trade union or consumer group, there were 10 with companies and industry federations. The rest of the meetings were with other actors such as public institutions and academics. In total, DG Trade met 288 lobby groups in the early phase of the TTIP talks – 250 of them from the private sector (Check the full data and how we gathered it here).

There is evidence that DG Trade actively encouraged the involvement of corporate lobbyists, while keeping pesky trade unionists and other public interest groups at bay. For example, in autumn 2012, DG Trade chased pesticide lobby group ECPA to participate in the then-ongoing public consultation on TTIP. As “the European crop protection/pesticides industry, is one of the key sectors we would be looking at in terms of improving the framework for business,” a DG Tradeemailed ECPA, their contribution “would be most welcome”. The official added: “A substantial contribution from your side, ideally sponsored by your US partner, would thus be vital to start identifying opportunities of closer cooperation and increased compatibility”. ECPA responded a few weeks later, together with its US sister organisation CropLife America, demanding “significant harmonisation” for pesticide residues in food. Trade unions, environmentalists, and consumer groups did not receive such special invites.

DG Trade’s responses to contributions to the public consultations also differed greatly. While trade unionists received a standard confirmation receipt, business lobbyists were invited to initiate follow-up meetings with negotiators. The Association of Automotive Suppliers (CLEPA), for example, got an email from DG Trade thanking “you for your readiness to work with us”, and offering a meeting, “to discuss about your proposal, ask for clarification and consider next steps”. Again, public interest groups did not receive this special treatment.

BusinessEurope and the US Chamber of Commerce, two of the most powerful pro-TTIP lobby groups, also had a follow-up meeting in November 2012, after responding to one of the Commission consultations on TTIP. On the table: their proposal for “regulatory cooperation”, a “potential game changer” which would allow business lobbyists to “co-write regulation”, as theyput it. At the table: officials from DG Trade, but also DG Enterprise and the General Secretariat of the Commission. The atmosphere was clearly friendly. And the Commission stressed its desire to work closely with the two business lobbies to refine the proposal (renewed in another meeting with BusinessEurope in February 2013 where the Commission noted the importance of EU industry “submitting detailed ‘Transatlantic’ proposals to tackle regulatory barriers”1). A year later, the EU negotiation position for regulatory cooperation in TTIP was leaked. The demands of the US Chamber and BusinessEurope had been largely accommodated – one example showing that, while the number of lobby encounters does not have a simple correlation with levels of influence, it is an indicator, and these encounters do pay off.

Another example of the formidable alliance between EU negotiators and the corporate sector is the enthusiasm in the financial lobby community for the EU’s approach on financial regulation in TTIP. When the EU’s position on the issue was leaked in early 2014, Richard Normington, Senior Manager of the Policy and Public Affairs team at TheCityUK – a key British financial lobby group – applauded the Commission’s proposals, because it “reflected so closely the approach of TheCityUK that a bystander would have thought it came straight out of our brochure on TTIP”.

So, clearly, the close involvement of business lobbyists in drawing up the EU’s position for the TTIP talks is a result of the privileged access granted to them by DG Trade. Despite her PR to the contrary, this practice hasn’t changed significantly under the new Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström, as the next info-graphic shows.

- 1.European Commission (2013): Brief report – BusinessEurope US Network meeting, 21 February 2013, dated 22 February 2013. Obtained through access to documents requested under the information disclosure regulation. On file with CEO.

-

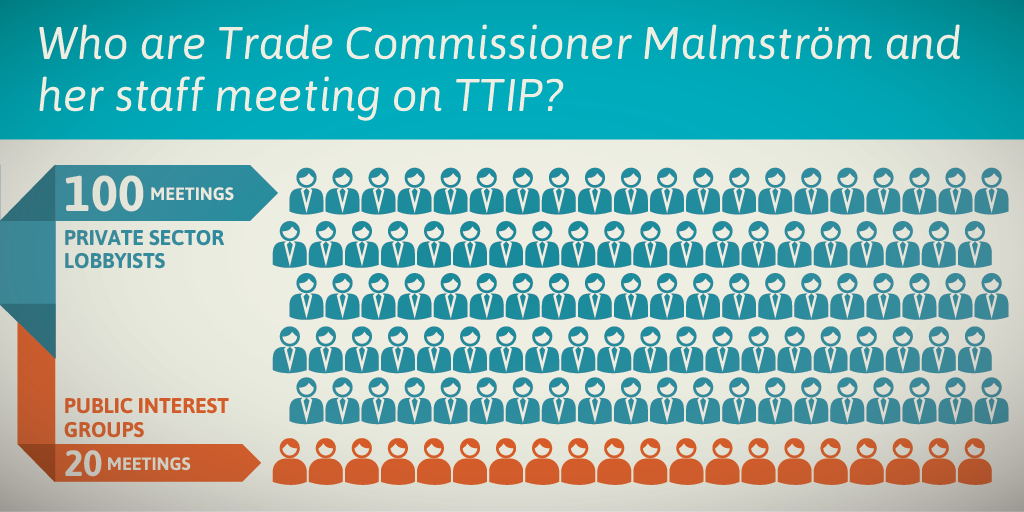

When European Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström took office in November 2014 she promised a “fresh start” for the TTIP negotiations, including more civil society involvement and listening to public concerns as her “top priority”.

So, have things changed since the early phase of the TTIP talks? Has the Commission’s consultation policy on TTIP become less business-biased under Malmström?

The short answer is no. In the first six months since Malmström took office, she, her Cabinet and the director general of DG Trade had 121 one-on-one lobby meetings behind closed doors in which TTIP was discussed. 100 (83%) of these declared meetings were with business lobbyists – but only 20 (16,7%) were held with public interest groups (the other meeting was with a standard setting institution). So, for every meeting with a trade union or an environmental organisation, Malmström and her staff had 5 get togethers with companies and their lobby groups. (Check the full data and how we gathered it here).

The lobby groups with the most such high level meetings on TTIP were the Transatlantic Business Council (representing over 70 EU and US-based multinationals), pharmaceutical lobby group EFPIA (lobbying for pharma giants like Eli Lily, Pfizer, Novartis, and GSK) and the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise. Second in line were BusinessEurope (the European employers’ federation and one of the most powerful lobby groups in the EU), the European Services Forum (a lobby outfit banding together large services companies such as Deutsche Bank and Telefonica, as well as federations like TheCityUK), CEFIC (the European Chemical Industry Council, lobbying for BASF, Bayer, Dow, and others), the German industry federation BDI, the Open Europe think tank, the French industry federation MEDEF, the European Roundtable of Industrialists (banding together together 52 bosses of European multinationals), the Confederation of Finnish Industries, and a Spanish law firm.

Transparency International’s Integrity Watch platform reveals similar findings, but counts only meetings in which TTIP was explicitly listed.

However, none of the figures tells the full story of lobbying around TTIP under Malmström: only Commissioners, cabinet members, and director general bosses are required to log their meetings with lobbyists while the TTIP negotiating team and other DG Trade staff aren’t required to do so.

Still, the fact that Malmström and her team seem to primarily deal with the arguments of business representatives raises serious concerns that industry lobbyists continue to dominate the agenda of the TTIP talks and crowd out citizens’ interests. This is supported by the cosiness between Malmström, her team, and big business, as is made apparent in correspondence such as this emailof Big Finance lobby group TheCityUK, inviting Malmström’s head of Cabinet to “informal lunch” “on her way back from the US”, with “plenty of time for whatever questions she would like to raise with us”.

There is also evidence that Malmström and her team are close enough to Big Business to discuss joint strategies and communication challenges. In a meeting with French employer’s federation MEDEF on 26 March 2015, for example, the lobby group warned that “the 19 million European SMEs which do not export… will face increased competition” from TTIP and asked Malmström and her team “how the (Commission’s) communication services can reassure” the small and medium enterprises.

Malmström’s move on controversial rights for foreign investors in TTIP, which closely follows the big business agenda, also reinforces the view of her close alliance with corporate lobbyists. In a blatant disregard for democracy, the Commissioner brushed off thousands who have spoken out against excessive corporate rights, a full 97 per cent of about 150,000 contributions to a consultation on ISDS – including small businesses and governments – in order to adhere to the corporate agenda on the issue.

These are the corporate lobby groups which had by far the most lobby encounters with DG Trade in the preparatory and early phase of the TTIP negotiations (January 2012 to February 2014):

- BusinessEurope, the European employers’ federation and one of the most powerful lobby groups in the EU.

- Transatlantic Business Council, a corporate lobby group representing over 70 EU and US-based multinationals.

- ACEA, the European car lobby (working for BMW, Ford, Renault, and others) which had as many lobby encounters with DG Trade as CEFIC, the European Chemical Industry Council (lobbying for BASF, Bayer, Dow, and the like).

- European Services Forum, a lobby outfit banding together large services companies and federations such as Deutsche Bank, Telefónica, and TheCityUK, with the same amount as lobby encounters as EFPIA, Europe’s largest pharmaceutical industry association (representing some of the biggest and most powerful pharma companies in the world such as GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Sanofi, and Roche).

- FoodDrinkEurope, the biggest EU food industry lobby group (representing multinationals like Nestlé, Coca Cola, and Unilever).

- US Chamber of Commerce, the wealthiest of all US corporate lobbies, and DigitalEurope(whose members include all the big IT names, like Apple, Blackberry, IBM, and Microsoft), both with the same amount of lobby encounters with DG Trade.

Check the full list of lobby groups and how we gathered the data here.

These big business lobby groups have a nasty record of fighting stricter safety and environmental rules to protect people and the environment in the EU. To take a few examples:

- FoodDrinkEurope has fought against consumer-friendly food-labelling.

- The chemical lobby CEFIC and its members have waged an all-out lobbying war against an EU initiative to ban endocrine (hormone) disrupting chemicals.

- DigitalEurope fiercely lobbied against EU data privacy laws.

- BusinessEurope has lobbied against EU legislation to ensure gender equality on company boards, to extend maternity leave, to reduce air pollution, as well as the Financial Transaction Tax intended to create financial stability against further crises – to name just a few initiatives on the employers federation’s hitlist.

Through the secret TTIP negotiations, these corporate lobby groups are now attempting to achieve by stealth what they could not attain in an open political process: a roll back of regulation intended to protect the public interest.

-

These business sectors had most meetings behind closed doors with DG Trade when the TTIP negotiations were being prepared and after negotiations started (January 2012 to February 2014):

- Agribusiness and food, including multinationals like Nestlé, Mondelez (formerly Kraft Foods), and Cargill as well as numerous lobby groups for producers and traders of food, drinks, and animal feed such as FoodDrinkEurope (the EU’s biggest food industry lobby group, representing multinationals like Nestlé, Coca Cola, and Unilever), Eucolait (the dairy traders’ lobby), Clitravi (lobbying for the EU meat processing industry), Spirits Europe (working for alcohol producers such as Bacardi-Martine and Pernod-Ricard) and FEFAC (the animal feed lobby).

- Lobby groups representing multiple business sectors such as the European employers’ federation BusinessEurope (one of the most powerful lobby groups in the EU), the US Chamber of Commerce (the wealthiest of all US corporate lobbies), the Transatlantic Business Council (representing over 70 EU and US-based multinationals) and national industry federation such as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) and the Federation of German Industries (BDI).

- Telecommunication and IT, including giant corporations such as IBM, Telefónica, Nokia, Google, and Ericsson as well as industry lobby groups such as DigitalEurope (whose members include all the big IT names, like Apple, Blackberry, IBM, and Microsoft).

- Pharmaceuticals, including direct lobbying of large pharmaceutical companies such as GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Johnson & Johnson, Roche and Pfizer as well as lobby groups such as EFPIA (the European pharmaceutical lobby working for pharma giants like Eli Lily, Pfizer, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline) and its US sister organisation PhRMA (lobbying largely for the same companies).

- Finance, with lobbying by some of the world’s largest banks and insurers (including Morgan Stanley, JP Morgan, HSBC, Allianz, and Citigroup) and powerful financial sector lobby groups such as the Association of German Banks (BDB), Insurance Europe (Europe’s main insurance lobby), and TheCityUK (promoting the interests of the UK-based financial industry).

- Engineering and machinery, including manufacturing behemoths such as Siemens, Alstom, and General Electric as well as industry federations such as Orgalime (lobbying for the mechanical, electrical and metalworking sectors) and the German Engineering Federation VDMA.

- Automobiles, with some of the most powerful car brands (including Ford, Daimler, and BMW) and automotive suppliers such as tyre producer Michelin, as well as industry lobby groups such as ACEA (representing Europe’s car, van, truck, and bus manufacturers) and the German automotive industry association VDA.

- Health technology, with, for example, Eucomed (representing the medical technology industry in Europe, including large corporations such as Siemens and Procter & Gamble), Cocir (lobbying for “medical imaging, health ICT and electromedical” companies such as IBM, Samsung, Orange, and Agfa healthcare “to open markets… in Europe and beyond”).

- Chemicals, including CEFIC (the EU’s biggest chemical industry lobby group, representing BASF, Bayer, Dow, and others) and its US counterpart, the American Chemistry Council ACC (also lobbying for BASF, Bayer, Dow, and others), the Germany industry federation VCI and direct lobbying by chemical giants such as Dow.

- Express & logistics, including direct lobbying by companies such as Deutsche Post DHL, UPS, Fedex and industry associations such as the European Express Association (lobbying for the same companies).

Check the full data and how we categorised it here.

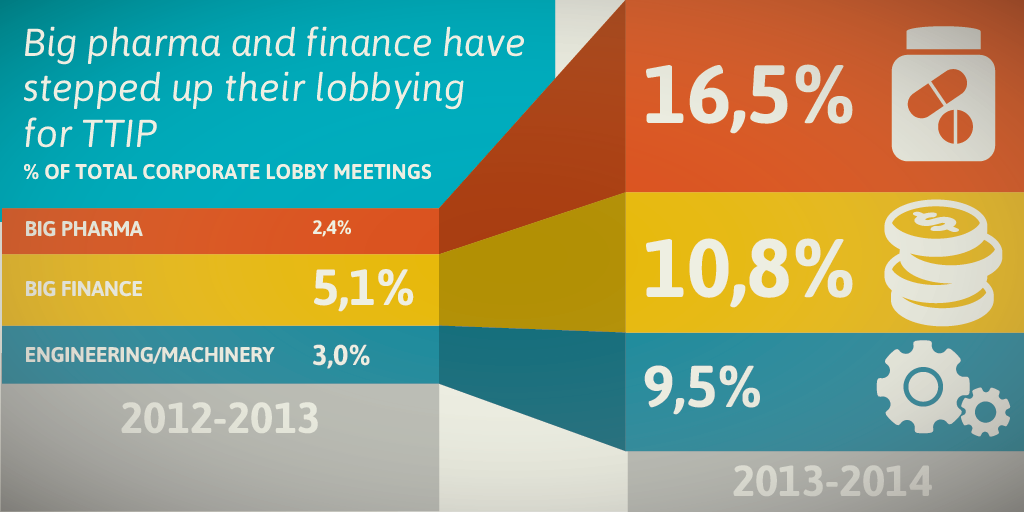

Several industry sectors have significantly boosted their lobbying efforts for TTIP:

- The pharmaceutical sector has increased its TTIP lobbying seven-fold. While only 2.4% of DG Trade’s one-to-one lobby meetings on TTIP were with big pharma in the preparatory phase of the negotiations (January 2012 to March 2013), the sector’s share in lobby meetings jumped to 16.5% in the period after (April 2013 to February 2014).

- The engineering and machinery sector has tripled its TTIP lobbying effort in the same period – from 3.0% to 9.5% of the behind-closed-doors meetings with DG Trade.

- TTIP lobbying by banks, insurers, and other financial market actors has doubled, from a 5.1% share in the total amount of corporate lobby meetings in the preparatory phase of the negotiations to 10.8% in the period after.

Check the full data and how we gathered it here.

That big pharma and finance have stepped up their lobbying for TTIP is particularly worrying. The pharmaceutical sector is pushing for a TTIP agenda with potentially severe implications for access to medicines and public health. Longer monopolies through strengthened intellectual property rules and limits on price-controlling policies in TTIP could drive up prices for medicines and costs for national health systems. The joint attempt of lobby groups EFPIA and US sister organisation PhRMA to limit EU initiatives for data disclosure from clinical trials could bury knowledge about the true effects of medicines (including their safety and evidence of benefits – or lack thereof) and hamper innovation.

The US administration seems to have taken the big pharma wishlist – on intellectual property rules and other issues – on board, as recent revelations about its position in the negotiations over the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with 11 other countries indicate – to the detriment of consumers. This is in stark contrast to President Obama’s agenda to encourage more cost-saving generic medicines within the US health system. As in the TTIP talks, big drug companies havemassively boosted their lobbying for TPP over time.

It’s a similar story with big finance. The financial sector has been remarkably candid in listing US and EU financial regulations that they would like to see scrapped via TTIP – from US rules on capital reserves (which require companies to keep aside a proportion of capital available to avoid risk of collapse or bailout), to regulations on too-big-to-fail foreign banks. Big finance on both sides of the Atlantic is also lobbying for a dedicated TTIP chapter on financial regulation, which could lead to the delay, watering down, or outright block of much needed reform and control of the financial sector necessary to avoid another financial meltdown, civil society groups have warned.

The EU’s TTIP proposals on the issue are indeed designed to prevent new financial rules from the other side of the Atlantic harming the interests of “market operators”, eg banks or hedge funds. The US administration, on the other hand, has expressed its opposition to agreeing to a TTIP chapter on financial regulation, concerned that the EU is taking aim at US rules. US Treasury Secretary Jack Lew, for example, has said on several occasions that he opposed the inclusion of financial regulation in the TTIP because, “normally in a trade agreement, the pressure is to lower standards on things like [financial regulation or environmental regulation or labour rules]”. He also said that the US would “not allow these agreements to serve as an opportunity to water down domestic financial regulatory standards”, or “dilute the impact of the steps that we’ve taken to safeguard the US Economy”.1

- 1.Inside US Trade; Lew Resolute On Excluding Financial Services Regulations From TTIP Talks, 20 December 2013.

While the corporate agenda for TTIP is broad and often issue-specific, big business is united in what it wants to see at the core of the agreement: excessive rights for foreign investors and regulatory cooperation. These issues would further skew EU and US politics in favour of capital and transnational corporations and threaten any future regulation that limits big business profits – be it in food standards, chemicals approval, or rules on production methods, to name but a few.

TTIP’s “regulatory cooperation” chapter would provide business groups with a series of tools to apply pressure on decision makers in Brussels and Washington as well as in EU capitals and US states to scare them away from adopting rules that would hurt business interests, often to the detriment of other groups in society. According to leaked EU proposals, corporate lobbyists would be offered new opportunities to “provide input” which “shall be taken into account” by policy-makers. New regulations would have to undergo an “impact assessment” with questions that are primarily tilted towards the interests of business, not citizens. Companies could also use EU-US exchange procedures to complain about an “envisaged or planned regulatory act”, and regulations under review. And they would be given an agenda-setting role in new transatlantic regulator-to-regulator bodies. (Read our more encompassing analysis of regulatory cooperation here or watch our video on the issue here.)

On top of that, TTIP’s investment protection chapter would empower thousands of businesses on both sides of the Atlantic to legally attack decisions made by national parliaments, governments, and even courts if they undermine corporate profits. Around the world, companies are already using the so called investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions to claim billions in compensation for perfectly legitimate government policies to protect health, the environment, and other public interests. Just the threat of such an expensive claim can be enough for policy-makers to abandon or water down a proposed or adopted law on public health and environmental protection. (See our analysis of the proposed investor rights in TTIP here or watch our video on the issue here.)

Taken together, the excessive rights for foreign investors and proposals for regulatory cooperation will significantly expand business power over politics across the EU and the US. The measures would make it easier for business to roll back regulation and block new rules intended to prevent the food industry from marketing foodstuffs with toxic substances, laws trying to keep energy companies from destroying the climate, or regulations to combat pollution, financial instability and protect consumers. No wonder, powerful business lobby groups like BusinessEurope and the US Chamber of Commerce see regulatory cooperation in TTIP as a “potential game changer”, a “gift that keeps on giving”, which would essentially allow business lobbyists to “co-write regulation”, as they put it.

The preparatory and early phases of the TTIP negotiations were largely driven by businesses with headquarters in the US, Germany, and the UK and by industry lobby groups organised at the EU level such as BusinessEurope. For the period between January 2012 and February 2014, we did not come across a single direct lobby encounter on TTIP between DG Trade and businesses from Greece, Cyprus, Malta, Portugal, and most of Eastern Europe (Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovenia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia).

This is in line with warnings that these countries will carry the weight of the social costs of TTIP as a result of the increased competition. With US export interests targeting mainly those sectors where the European periphery has defensive interests – such as agriculture – the opening up of the EU to more transatlantic competition is likely to exacerbate the divide between the EU’s economic core and its periphery, in other words: the EU’s richer and its poorer countries. It seems that businesses in the poorer EU countries have little to gain from TTIP and are therefore not pushing for the deal.

Here you can see how many corporate actors lobbied DG Trade on TTIP in the period between January 2012 and February 2014, listing only the countries with more than 5 actors lobbying:

Country of origin

Total number of corporate actors

EU-level business lobby groups

115

US companies & industry associations

89

German companies & industry associations

28

UK companies & industry associations

25

French companies & industry associations

18

International lobby groups

16

Danish companies & industry associations

10

Spanish companies & industry associations

10

Dutch companies & industry associations

8

Swedish companies & industry associations

8

While the above figures relate to the total number of lobby encounters – meetings behind closed doors, contributions to public consultations, and stakeholder meetings – US businesses jump to the top of the list when considering only the one-on-one meetings with DG Trade: in the early phases of the TTIP negotiations, DG Trade met 78 US-based companies and industry federations – compared to 66 EU-level lobby groups. This reflects the strong presence of US corporations in the top-10 biggest spenders on EU lobbying, with ExxonMobil, Microsoft, Dow, Google, and General Electric all spending more than €3 million per year on lobbying the EU institutions.

Check the full data and how we gathered it here.

One in every 5 corporate lobby groups which have lobbied DG Trade on TTIP (80 out of 372 corporate actors), are not registered in the EU’s Transparency Register, amongst them large companies such as Maersk, AON, and Levi’s. Industry associations such as the world’s largest biotechnology lobby BIO, US pharmaceutical lobby group PhrMA, and the American Chemical Council are also lobbying under the radar. More than one third of all US companies and industry associations which have lobbied DG Trade on TTIP (37 out of 91) are not in the EU register. (see the full data and how we gathered it here)

Also, several lobby groups who have lobbied DG Trade most actively in the early phases of the TTIP talks do not list the agreement amongst the important issues they are currently lobbying on in their Transparency Register entry. 1So, for those who want to find out who is lobbying on TTIP and what amount they spend to make the deal happen, the register provides few to no answers.

This indicates two serious flaws of the EU’s Transparency Register: first, it is voluntary, which leaves companies and lobby groups free to avoid appearing in it – as many do. Second, disclosure requirements are limited as registrants are, for example, not obliged to report exactly which specific issues they lobby on (such as TTIP).

But the public has a right to know who is lobbying for TTIP, how many lobbyists are involved, and how much money they spend. Only a mandatory register which requires comprehensive and reliable information about lobbying will shed light on corporate lobby pressure behind the TTIP talks. The EU must make its lobby transparency register TTIP-proof!

- 1.For example, European employers’ federation BusinessEurope, digital technology lobby group DigitalEurope, and pharmaceutical lobby group EFPIA.